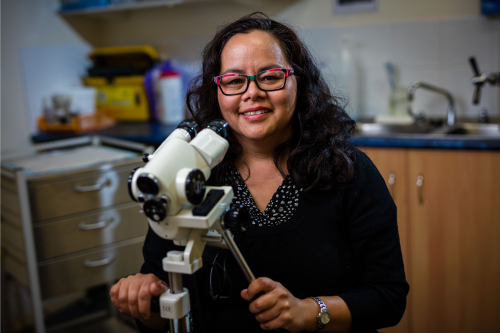

AIDA member Dr Marilyn Clarke is Australia’s first Aboriginal obstetrician and gynaecologist. Her journey into medicine began with a campus tour and has become a career defined by visibility, leadership and cultural strength.

“I was really good at maths, so I thought I might be an accountant,” she said.

That changed during a school excursion to the University of Newcastle, a national leader in supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students into medicine.

There, she met medical students Sandra Eades and Lewis Peachey – the first Indigenous graduates in the University of Newcastle medical program – who are now leaders in the field.

“That was the first time the penny dropped in my head that maybe I was smart enough to do medicine,” she recalls.

“I very much believe in the philosophy that you can’t be what you can’t see.”

Dr Clarke went on to become the first in her family to complete Year 12 and go to university.

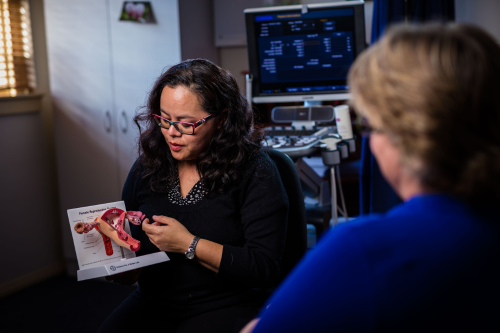

Today, she lives and works on Gumbaynggirr Country where she specialises in obstetrics and gynaecology.

Representation in Practice

When Dr Clarke entered her specialty, she was the only Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Fellow in the field.

“I was the first in that specialty and now we have quite a few coming through,” she shares.

“I hope that me being the first in the field was what allowed others to say, hey, I can do this too.”

That visibility has had a significant impact, particularly for patients.

“The number of times that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients see us and the joy they have is immense,” she said.

Dr Clarke’s influence also extends to policy and practice. She has worked closely with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) for more than a decade.

“The bigger impact is actually having a voice and being at the table around policies, having an influence in college, having an influence on the health system and how it’s delivered and making it safer and more culturally safe for our patients,” she said.

“Now we’ve got the lived experience, and we bring a lot of wisdom to the table.”

Supporting Strong Health Leadership

Dr Clarke believes medical students, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous, should be trained as leaders, not only clinicians.

“I don’t want you coming through this to just be a good clinician,” she said.

“I want to produce a great health leader who is going to be passionate about health equity and being a strong ally and advocate because that’s part of the job description.”

In 1997, there were just 24 known Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors in Australia. Today, that number has grown to 921. While this represents just 1 per cent of the medical workforce, it reflects decades of collective effort and determination.

While the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors continues to grow, representation in specialist training remains limited.

For example, only 12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander trainees are currently recorded with the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

This reflects the continued need for culturally safe training pathways, peer support and visibility at all stages of a medical career — an approach supported by AIDA.

Shaped by Strong Women Role Models

Dr Clarke’s passion for obstetrics and gynaecology is grounded in lived experience.

Her mother was a midwife and one of the first independent women’s health practitioners in New South Wales. She delivered holistic care through women’s clinics that looked beyond symptoms to the person.

She also credits Sister Alison Bush, a senior Aboriginal midwife at King George V Hospital in Sydney, for mentoring her and her sister during their medical studies.

“She really took us under her wing and inspired that passion to do obstetrics and gynaecology because of her passion,” she said.

“Another demonstration of how important role models are.”

Over the past two decades, Dr Clarke has witnessed positive change in her specialty.

“In the early days, I saw a lot of women who were passive recipients of care, often not well informed about what was happening to them and their bodies,” she shares.

“Now, women are health consumers, having their voices heard and becoming active participants; that gives me a lot of joy.”

Supporting the Next Generation of First Nations Doctors

Dr Clarke is deeply committed to supporting the next generation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors and health leaders.

“Find what it is that inspires you and gets your fire burning,” she said. “You need that in this field so follow your passions.” Her journey reflects the strength, leadership and cultural knowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors bring to health care across Australia.